The problem

Since the rise of modern self-help culture, fiction is often looked down upon. It’s frequently seen as a waste of time, as lacking practical value, or as something purely meant for entertainment.

I personally believe that this is wrong, and that fiction is highly beneficial. Furthermore, I suspect that it would be profoundly detrimental to the human species if the importance of great fiction were forgotten. That’s why I want to make a case for the value of fiction and explore how it actually benefits us.

How fiction affects us

To do this I must first explain how fiction affects us, because it doesn’t feel very life-changing.

Good non-fiction can lead to immediate “aha” moments when you learn something. But when you read a story, you don’t feel like you’ve “learned” anything, you’ve just followed along. But, that’s where the magic happens. “Following along”.

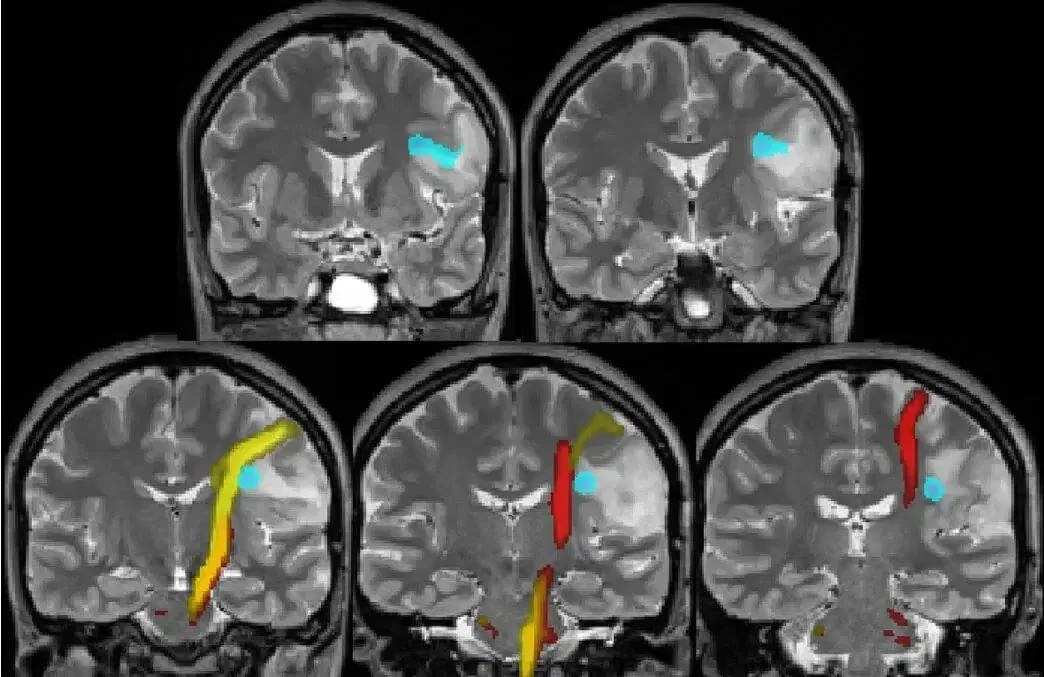

There are well-established fMRI studies showing that when we read narrative stories, the brain partially activates the same regions that would be active if we were physically or emotionally experiencing what the character experiences.

example of fMRI imaging

In other words, our brains are imitating what the character in the story goes through. Regions involved in vision, hearing, bodily sensation, movement, and emotion all show activity during story-reading. This doesn’t mean the brain can’t tell fiction from reality, it means stories work through simulation rather than conscious instruction.

On the other hand, when reading non-fiction, the brain primarily engages areas related to language processing, analytical reasoning, and factual encoding.

I’m not trying to prove that fiction is better than non-fiction here, only that fiction works in a less obvious way. Non-fiction feels useful immediately because it speaks to conscious reasoning. Fiction works more quietly, using imagination and deeper, pre-reflective layers of the mind.

Now my belief is that when these parts of our brain imitate the characters in the story, we are learning as well, but just silently. We start to learn from their ways of thinking, acting, and responding to the world.

It’s no coincidence that watching a hero confront evil can leave us deeply stirred. Or that young children learn true courage, loyalty, or self-sacrifice first through stories rather than through advice.

A curious but revealing phenomenon

There’s another important observation here. Even non-fiction rarely communicates through facts alone.

Self-help books rely heavily on anecdotes. Philosophy uses thought experiments. Science explains ideas through metaphors and examples. History becomes meaningful through biographies rather than timelines.

If pure information were enough, these stories wouldn’t be necessary. But they are, because stories are how human beings remember and integrate information.

Non-fiction often smuggles in stories to make its message stick. Fiction, by contrast, is honest about what it’s doing.

Distinguishing good and bad fiction

I need to make an important distinction. If we learn from characters, and maybe even imitate them, consciously or unconsciously, then what we read matters. We want to learn the most virtuous path in life, and not be led astray. So, we must choose wisely what fiction we read.

I see two types of fiction as especially valuable, one more so than the other:

- Fairy tales

- Fiction that has withstood the test of time

These are both credible due to their age. But fairy tales far more so. Most people assume that fairy tales are only a few hundred years old, because that’s when they were first written down. In reality, many fairy tales have existed for thousands of years. Most existed as oral traditions, passed down generation to generation.

Because they were retold generation after generation, details changed, but core patterns remained. Over time, this produced what we call archetypes.

By archetypes, I mean:

- recurring roles or deep patterns,

- recognisable shapes of human experience,

- things we intuitively understand before we can explain them.

Examples include:

The Hero: leaves safety, confronts evil, suffers, and returns transformed. Think of Harry Potter or Frodo in The Lord of the Rings.

The Mentor: offers guidance but does not walk the path for you. Think of Gandalf, Dumbledore and even Yoda.

The Shadow: corrupted desire, chaos, or evil. Sauron, Voldemort, the Joker.

The Sacrificial Innocent: suffers for the sake of others. Jesus Christ (fulfilled in reality also), Neo.

At this point, a common objection usually arises: “I think I understand what you’re saying, but it’s still not real. These archetypes aren’t real people.”

This objection usually rests on a narrow understanding of truth. Specifically, an understanding of truth limited to historical or empirical fact. A story can be factually untrue and yet structurally true, and thus be a meta-truth.

Harry Potter did not exist as a historical individual. That much is obvious. But the pattern he embodies, the courageous hero who accepts suffering, breaks rigid rules for the sake of the good, and chooses love over power, has occurred millions of times throughout human history.

Fiction does not tell us what happened once; it tells us what keeps happening, again and again, wherever human beings live and act.

In this sense, archetypal stories are not less true than factual reports or non-fiction; they are, in a meaningful way, hypertrue. Not because they describe events with historical precision, but because they describe patterns that recur across human life consistently.

Other fiction is filtered over time in the same way as fairy tales. Stories that contain deep truth endure. Those that don’t, fade. We as a civilisation stop reading them, and recommending them to peers. And they slowly die.

Given some time, only the most true fairy tales and stories, those containing the most recognisable archetypes, stay alive. That’s why works like The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, The Chronicles of Narnia, or 1984 continue to move people.

Learning from good and bad archetypes

One last thing I want to add is that bad archetypes can be just as valuable. When we engage with strong archetypal stories, we can learn how to act, or how not to act.

We can learn just as much from detestable characters as from honourable ones. Just like children learn to not trust charming strangers (the wolf) and be overly curious when getting told the story of Little Red Riding Hood.

Final advice

In conclusion my final advice is simple:

Don’t be afraid to spend time reading fiction. It may not feel immediately useful, but it quietly trains imagination, character, and long-term moral vision.

And as a final note: fiction is also highly relaxing. So we don’t merely learn a lot subconsciously, but we can also get some well-deserved rest. A rare case where these don’t exclude one another.